My 1995 main stage TEDTalk from 1995 was on a cassette tape. In those days, only audio was recorded. A friend digitized it and I thought it would be fun to post here. When David Letterman had a late night show in the 90’s, he always featured a Top Ten list. In 1995, the technology and media industries were still in the early days of pioneering multimedia content. There was a growing pile of what was referred to as “shovelware.” My 1995 TEDTalk offered insights on the evolution of digital content and was in the style of Letterman Top Ten list.

Does Constant Multitasking Lead to Digital Dementia?

In 1996, I was working at Microsoft in Seattle and teaching a graduate student seminar at NYU in the Interactive Telecommunications Program. I noticed that at Microsoft, some of my colleagues had two screens, but each screen only had one thing running; either email, a spreadsheet, or a word processor. At NYU, students had one screen and it was tiled with open windows: instant messaging, email, chat, and more. In many cases, the students were also carrying pagers and cell phones, and juggling the many incoming communications.

In the media, there was already a conversation about multitasking, but what I was witnessing went far beyond the simple multitasking that people were fretting over. With simple multitasking, we are engaging in an activity that’s automatic (like stirring soup, tying a shoe – anything that we can do without taxing ourselves mentally), and another activity that is somewhat mentally taxing (a phone conversation, writing an email, etc). Many moments, most days, involve a lot of simple multitasking.

What I witnessed people doing was beyond simple multitasking, and in order to differentiate it from simple multitasking, I gave it a new label: continuous partial attention. We were continuously paying partial attention to more than one activity that was mentally taxing.

With continuous partial attention, we engage in two or more activities that are mentally taxing (also called cognitive load). For example, we are writing an email and having a phone conversation.

Both in the case of simple multitasking and continuous partial attention, we are not doing these tasks simultaneously. We are rapidly task switching. Thus, the “myth of multitasking.”

With continuous partial attention, as we rapidly task switch, we experience more physical and mental stress. When we do this day after day, for hours on end, and, often attempting to do multiple activities on multiple screens, our body experiences a chronic fight or flight state, or stressed state (there are a number of posts, videos, and a FAQ on my website that explain this more fully).

A recent Stanford study suggests that heavy multitasking contributes to reduced memory, decreased ability to focus, compromised reasoning, and sleep and mood changes.

In 2012, German neuroscientist, Manfred Spitzer, created the term, digital dementia, to describe the health costs resulting from the chronic stress, multitasking, and compromised breathing we do when we work with personal technologies.

Since 1996, I’ve been speaking and writing about attention, technology, and health. We intend to do our best to manage our time online, to take breaks from our smartphones and screens and to get up frequently to move, and give our eyes and bodies a few minutes of recovery time during the course of a day. But. We. Don’t.

How can we better support ourselves given that we are likely to keep multitasking? What activities might serve as antidotes to digital dementia?

My favorite antidote is partner or ballroom dancing. There is preliminary research suggesting that ballroom dancing can decrease your risk of dementia by 76%. Ballroom dancing is physically, socially, and mentally challenging. Compared with walking, dancing has been associated with reduced brain atrophy in the hippocampus – a brain region that is key to memory and functioning.

Social partner dancing reduces social isolation and inactivity. It’s one of the most restorative activities we can do to minimize the health costs of multitasking, continuous partial attention, and hours in front of screens.

Here’s a recent CBS interview with Dr. Jon LaPook on multitasking and ballroom dancing.

https://www.cbsnews.com/amp/news/multitasking-myth-research-expert/

“Dance is the joy of movement and the heart of life.” — unknown

Is it Time to Keep a Kazoo Next to Your Computer?

It turns out humming offers many health benefits. The benefits include: relief from stress and anxiety, decrease in heart rate, increase in lymphatic circulation, increase in nasal nitric oxide, and vagus nerve stimulation.

A few months ago, I was on a call with one of my favorite neuroscientists. I had been reviewing a set of draft documents for someone else and was a little stressed about the material. I jokingly mentioned that I knew humming would be a good stress break. He said, “Even better, keep a kazoo next to your computer.”

I bought a kazoo and quickly noticed that in addition to all the benefits of humming, a kazoo also works your abdominal muscles (depending on the tune you choose; try Yankee Doodle or John Jacob Jingleheimer Schmidt).

Manoush Zomorodi on the NPR Body Electric, Season 2, Episode 12, included a short episode here on using a kazoo for a 5 minute screen break.

For more information on the benefits of humming, you can check out this book: THE HUMMING EFFECT, by Jonathan and Andi Goldman.

Happy Humming!

Screen Apnea: Our Bodies on Personal Technologies

Linda Stone spoke with NPR’s Manoush Zomorodi on a recent episode of Zomorodi’s podcast, Body Electric. Stone coined the terms, “Screen Apnea” and “Email Apnea” in 2008, after noticing she was holding her breath or shallow breathing while working on personal technologies. She looked around, and noticed most people were doing what she was doing: poor posture + poor breathing while using personal technologies.

“I would inhale with anticipation, but I wouldn’t exhale because so many emails would be streaming in,” Stone recalled. “And this would go on for hours.”

Listen to the full episode here.

NPR’s The Body Electric Investigates How Personal Technologies Impact Our Bodies

In one of the best series yet on technology and how our bodies and minds are taxed by our current habits, Manoush Zomorodi, interviews a variety of experts. Manoush kicks off the series with a challenge to NPR listeners to join a Columbia University/NPR study. Participants are tasked with getting up and moving for five minutes for every thirty minutes of time in front of a screen. Twenty thousand listeners accept the challenge and Manoush checks in with participants and with exercise physiologist, Keith Diaz on findings.

No surprises here! Everyone reports feeling better with consistent movement breaks.

Most of us don’t move nearly as much as our bodies would prefer. Our vision, posture, strength, and mental health all improve when we intentionally add more movement, and more break time into our day.

In 2007, I noticed that when I sat down in front of my computer screen, I would breathe more shallowly or hold my breath for extended periods. I called it email apnea or screen apnea, did informal dining room table research, and did a lot of wandering around, observing, and noticing to see if others were doing what I was doing. Screen apnea is easy to observe because one’s posture is compromised in a way that makes it nearly impossible to breathe optimally.

In 2008, I wrote about email apnea for the Huffington Post. This is still being discussed today, 16 years later!

The advice is the same in the wonderful NPR Body Electric Series, as it was in 2008. I’d like to add two activities that I hadn’t considered 16 years ago. The first is ballroom dancing. It’s great for posture, great for a sense of rhythm, and as an added bonus, brain health improves.

Another, newer activity, for me, especially now that so many people work from home, is playing a kazoo! When you get up to take a movement break, as you walk around, play a kazoo. The act of humming is great for calming the nervous system, it vibrates the bone structure in the face and head and stimulates the vestibular system, involves deeper breathing, and playing the kazoo works abdominal muscles. As an added bonus, it’s silly and fun.

“Linda Stone’s Antidote to Quantified Self: The Essential Self”

Originally posted by Wade Roush at Xconomy.com in 2014.

Linda Stone’s Antidote to “Quantified Self” Tech: The Essential Self

The Quantified Self movement emerged in the late 2000s in response to an absence: the lack of useful data about our bodies as we move through the day. Before the QS era, an EKG could show you your heart rhythms; a lab analysis could show you your cholesterol levels; a treadmill stress test could measure your general fitness. But these tests were expensive, infrequently administered, and hard for non-physicians to interpret. The first generation of commercial QS technologies, from companies like Nike, Fitbit, Polar, and Garmin, were a big step forward because they started to put health and fitness data directly into the hands of consumers.

But the Quantified Self approach to health is also defined in large part by an absence—that is, by what it ignores. QS is all about sensors like scales and accelerometers. These sensors produce numbers; the numbers must be interpreted by your thinking brain; and only then can they inform decisions about your body. It’s all several steps removed from your lived experience.

To put it another way: a fitness-tracking watch can tell you how far you’ve walked today, but it can’t tell you how you feel. What if the self your devices are quantifying isn’t the same person who feels hungry or sated, energetic or tired, happy or sad? What if it isn’t your essential self? And why are we collecting all this data, anyway? Is it helping us bring meaning into our lives?

Those are the kinds of questions Linda Stone, one of the 19 original Xconomists, has been raising lately in a series of recent talks and Web posts. And it was the main theme on the table when I interviewed Stone over lunch last week in Kendall Square.

Sometimes our five old-fashioned senses are more helpful than any amount of data, Stone argues. On the lecture circuit and in pieces for outlets like the Huffington Post and O’Reilly Radar, she’s described the essential self as “that pure sense of presence”—what our bodies are telling us about our experience in the physical world right now, without displays and readouts and spreadsheets in the way. Stone isn’t necessarily saying that we should eject monitoring technology from the equation. She’s just asking what might happen if these technologies were redesigned to give us direct sensory feedback, in a way that might serve the essential self, or what she calls embodiment.

This turn to slightly squishy notions about presence and embodiment might at first seem surprising, coming from someone who’s long been one of the country’s leading thinkers about the relationship between humans and computers. After all, Stone spent seven years working on multimedia technologies at Apple and nine years at Microsoft Research studying virtual communities and computer-mediated social life; she’s best known for originating the concept of continuous partial attention, the technology-exacerbated pattern of being superficially attentive to many different inputs without fully alighting on any of them.

But once you learn a bit more about Stone’s recent experiences, it’s easier to see where her questions are coming from. In 2004, due to surgeries related to a jawbone infection, she was afflicted with trigeminal neuralgia, a form of facial pain said to be one of most excruciating conditions known to medicine. During this period, all of Stone’s former competence at self-tracking went out the window, she says. When the data is troubling and chronic pain is an issue, she found, streams of health data can be frustrating and overwhelming.

Stone says she realized that Quantified Self technology is designed for people who are already healthy, not for those who are trying to heal. It occurred to her she’d be better off if she stopped focusing on the data and did a better job of listening to her body, using breathing and meditation to manage the extreme pain.

“My mind couldn’t direct my body to get better,” Stone told an audience at the MIT Media Lab earlier this year. “My mind and body needed to be friends. They needed to be partners in health. There might be a way to contribute to that through technology, but Quantified Self technologies did not feel kind, and I wanted to do things for my body that were kind. ”

Any technology that proposes to connect us to our essential selves, Stone argues, should speak directly to our senses through sound, light, vibration, and other stimuli. As an example, she cites devices like the HeartMath emWave, a heart rate variability monitor that uses lights and computer graphics to help users control stress levels. Computer users can clip the emWave lead to an earlobe while they work, and use cues from the software to remember to take an occasional break to de-stress.

While Stone’s ideas about the Essential Self are still at the early, theoretical stage—without scientific studies to back them up—she says her audiences are getting excited about the new apps and devices waiting to be built and the opportunities waiting to be explored. Ultimately, Stone says she’d like to see the Essential Self development into a movement alongside the Quantified Self—not replacing it, but supplementing it. “The question is: in what context are the numbers more helpful than our senses?” she writes. “In what constructive ways can technology speak more directly to our bodymind and our senses?”

Prior to our lunch, I hadn’t seen Stone since 2004, when I attended a social computing symposium that she co-organized for Microsoft Research (years before “social media” became a commonplace concept). She still lives in the Seattle area, but she stopped in Kendall Square on her way to the Media Lab, where she’s on the advisory board. Below is an edited writeup of our conversation.

Wade Roush: Can you say a bit how your thinking about the “Essential Self” emerged from your own experiences with illness and recovery?

Linda Stone: What I realized was that I could heal when my mind and body were not at war. I started to think about if there were technologies for embodiment, what would there be?

But even before that, when I was in the midst of dealing with this bone infection, I was getting chronic respiratory infections, and my doctor suggested that I take a breathing class. So I went and worked with someone who taught something called Buteyko breathing. And I went home with the exercises and I would dutifully walk as far as I could every morning and then sit down and do the Buteyko breathing exercises. Then I’d go to the computer to respond to e-mail and do some writing, and I’d get to the computer and I’d realize that I wasn’t breathing—that I was shallow breathing or breath-holding, and that my posture had changed from a posture that would allow me to breathe, to a posture where I was absorbed by the computer.

I began to think of the computer as a prosthesis of mind. And I wanted it to be a prosthesis of being. I wanted to bring my full self to it, my breathing self—the part of me that can think clearly and is fully engaged, and not just the part of me from the neck up.

I wanted a different relationship with technology. So as I became aware that I was shallow-breathing or breath-holding when I was at the computer, I got very interested in why that was happening, and what I could do. But I also started observing and talking to a lot of other people, and informally talked to and observed over 200 people in a seven-month period. I also talked to researchers at NIH and physicians and body workers and all kinds of people. And what I learned is that first of all, once we are on a smartphone or at a computer, one of the things that happens is we typically go into this posture [at this point Stone slumped her body forward]. We are thinking hard. We lose our body when we are thinking hard, in most cases. When we are at a smartphone we’re curled up around the smartphone, rapidly texting or typing. So again we lose ourselves into our minds.

I ultimately named that e-mail apnea or screen apnea. I talked to a lot of people about what is physiologically happening when we’re breath-holding or shallow-breathing. And I became interested in heart rate variability technology, because it can give you a sense of how stressed when you are at the computer. So I would use a HeartMath emWave heart rate variability ear clip, or something called an autonomic biometer, and I would use those things to just visually track stress. They use light and visual indicators to indicate that you’re stressed or not stressed. I would be able to see that out of the corner of my eye while I was working, and it would remind me to get up.

As I looked further into this, the other thing that I learned is that when you are sitting for periods of time your body doesn’t pump lymph very effectively. People talk about how sitting is the new smoking. And people also separately talk about needing to do a lot of detoxing. Well, the body is perfectly capable of detoxing, but it requires us to move. In the lymphatic system, the pump is your muscles, the calves of your legs. When you’re sitting you’re blocking the inguinal canal, you’re blocking the cisterna chyli, which is a major lymph area in the chest, and your body doesn’t have the resources it needs to pump lymph.

So we’re holding our breath, going into a fight-or-flight state, not pumping lymph, and becoming impulsive and spinning around how much we have to do, and it takes us to this very stressed place. And then we add Quantified Self technology! Not only are we putting ourselves in this stressed state, but we have all kinds of devices that are tracking and measuring, and we have technology telling the mind to tell the body how to be a better body. And we haven’t resourced the body one lick through the whole thing.

WR: One response would be to pull back from all this technology and go off the grid.

LS: That is one response. But there is another way to think about this, which is, how do we come to a place of embodiment in our lives and in everything we do? So it’s not about what we’re disconnecting from, it’s about what we are connecting to.

I think there are multiple paths to embodiment and to meaning. We are also talking about happiness. And we’re using happiness trackers, for god’s sake. I think that the real conversation is about meaning; it’s not about happiness. Happiness is an outcome of meaning. But if you’re going to talk about happiness, the question is how are you happy, not are you happy. “Are you happy?” leads you into an existential abyss. “How are you happy?” takes you exactly to the present moment where I can look at you and say, “This water tastes great, it’s fun hanging out,” and I’m not comparing it to thousands of moments to see if I am truly going to get a point for happiness.

WR: Is there a technological answer to this technological problem of letting the mind dictate to the body?

LS: Well, there’s a technological answer and a non-technological answer. Because at the heart of it all is embodiment. Who is embodied today? Athletes. Test pilots. Performance musicians. Performance dancers. They know how to breathe, how to move, how to feel their bodies. And what are we removing from school curriculums so that we can get to the “core”? We are removing art and music and dance and things that we think are a decorative fringe on the curriculum. They are not—they are the things that make us human.

Technology today goes from the technology to the mind to the body, and the body is a sort of victim of the mind and the technology ganging up on it. And the opportunity is to look at technologies for embodiment. What might those be? Well, it turns out that pulse and vibration and music and light and weight and temperature are all technologies that contribute to a sense of embodiment. So there’s one technology that I really like called Focus@Will, where a composer and a neuroscientist tested music to see if they could find patterns that would support a sense of engaged attention. Engaged attention is usually also accompanied with a sense of embodiment, and they created Focus@Will, which is a subscription music service. JustGetFlux is another tool, which changes the brightness and color or your computer screen to support circadian rhythms.

There are technologies coming out that support breathing, but a lot of those are still mediated through the mind. They fall somewhere between quantified self and essential self. The technology that I think is really interesting for breathing is the one that you might have in a belt buckle or on your belly that syncs up with your breathing and then slows its breathing, so it’s all a sensed experience. MIT Media Lab graduate Kelly Dobson created something like that called OMO.

WR: I’m guessing that soon as the Apple iWatch comes out, there’s going to be a temptation on the part of developers to build a million new Quantified Self apps that are not going in the direction of embodiment, but in the direction of numbers and the mind.

LS: I think Quantified Self apps are great for people who are healthier, who want to push themselves to walk five more steps. But more and more we’re hearing about people who are in chronic pain or who are sick. People who are healthy can game up whatever they want to game up and they can count whatever they want to count— until they get sick and they can’t. It might happen from a bicycle accident or it might happen from flu or bronchitis or something that sets them aside. And the first thing that happens when a quantified person gets sick is this war. The war is: My mind was running things and that was working, so why is my body betraying me? I’m smart. I followed the rules on nutrition. I followed the rules on exercise. Why me? “Why me” doesn’t make for that peace between body and mind.

WR: Do you feel like your Essential Self theory is starting to resonate and perhaps inspiring people to build technologies and apps that would support embodiment?

A: The message is so resonating. Every time I give a talk I get contacted, both by people who are doing Quantified Self technologies and who want to move toward Essential Self, and by people who want to talk about ideas for Essential Self technologies. People are realizing that counting is just another thing to do, and that where they feel soothed is by sensing and feeling. It’s why we end up sending cute cats to each other across the Internet. It’s soothing, it makes us happy, it feels good.

One of the things I learned as I researched attention is that attention, emotion, and breathing are very connected. If you are breathing in a relaxed way, you have an ability to use your attention exactly as you want to use it. Notice that a really good golfer is breathing. A good test pilot learns how to breathe to handle the G-forces. A good athlete can do that long-distance run because they know how to manage their breath and their emotion. Once you start holding your breath the stress starts.

So again, I think we need to change up the kind of questions that we’re asking ourselves. You know, it’s not “Do I want to be happy?” It’s “How am I happy?” And even more important, “Is there meaning in my life?” and “What moments feel meaningful?” It can be really little. It can be that you’ve said hello to a neighbor. Let’s talk about that, instead of talking about disconnecting and unplugging and distraction. Which is frankly a super stressful conversation, don’t you think?

WR: The idea of having to turn off or give up my devices is stress inducing all on its own. I feel like I need them to be as productive as I am.

LS: We have this naming, blaming game that goes on, with television and junk food, and now technology is the evil thing. But at the scene of the crime, the thing that’s in common is us. And so what is our opportunity? It’s to determine what we want to connect to. One of those things is coming back to embodiment. Coming to our senses, so to speak.

I guess the last piece of this is, in the same way that we have a physical homeostasis, we have a spiritual homeostasis, both individually and collectively. When we move so far away from where we are comfortable with who we are as human beings, we are drawn to what soothes us and makes us more comfortable. And there are four dominant collective activities that I see that are very soothing and that are bringing us right back.

First, the move toward yoga and meditation. Second, the maker movement, which is almost like a meditation movement—it brings us to our own creativity and resources with a kind of relaxed, engaged attention that is like children at play. Third, the urban gardening movement. Fourth, the movement toward joyful dance as exercise, from African Dance to Zumba to Nia to Continuum. Dance and rhythm are among the most powerful ways for us to re-set our individual and collective nervous system; this is a really powerful trend that contributes to our collective health and well being. I think these four things are all the same thing, and they’re all returning us to this spiritual homeostasis.

By Wade Roush at Xconomy.com, 8/8/2014.

Screen Apnea in the NYTimes

In 2007, I made some observations and named what I was seeing in a 2008 Huffington Post article. I described a phenomenon I initially called email apnea, and later referred to, interchangeably as email apnea or screen apnea. This followed observations and research I’d done in the 1990’s on attention, when I coined the phrase, “continuous partial attention,” in an effort to differentiate between simple and complex multi-tasking.

So many people recognized both continuous partial attention and “screen apnea” in themselves and resonated. I’m especially grateful to Steve Porges, Fred Muench, and Margaret Chesney, who, early on, helped steer through related research on breath holding and shallow breathing. Dr. Porges and Dr. Muench helped me understand the physiological impact of what I was noticing as well as the relationship to the vagus nerve and vagal tone. I love that the journalist, Alisha Haridasani Gupta, features Dr. Porges’ insights. I’ve come to believe that exercises that contribute to healthy vagal tone are as important as breathing exercises.

Here’s the link to today’s NYTimes piece.

30 pounds of Air Every Day

According to James Nestor, the author of Breath: The New Science of a Lost Art, “We get most of our energy from our breath, not from food or drink. Our bodies process about 30 pounds of air every day, compared to only a few pounds of food and water. There’s a reason why you can survive weeks without food, days without water, and only minutes without air.”

It isn’t easy to breathe properly. Proper breathing is slow – fewer inhales and exhales per minute, with the mouth closed. Breathing through the nose allows the nose to filter out mold, bacteria, and dust. It also helps the body produce, in the sinuses, nasal nitric oxide, which is antibacterial, antiviral, anti-fungal, and anti-pathogenic.

In 2007, I started doing ten minutes of breathing exercises every morning. Some mornings, I would go to my computer to check email right after doing the breathing exercises. I noticed that as soon as I sat down in front of the screen, my breathing was compromised. I was either holding my breath or breathing shallowly. The wonderful sense of peace and presence the breathing exercises created, dissolved into stressful thoughts, “There’s too much to do! I can’t get this done! I’m so behind!”

I wondered if this was just me or if it was more widespread. I observed people in offices, cafes, and on their phones. Screens tend to consume us. We stoop forward, round our shoulders, bring our eyes in closer to the screen, chest concave. Try sitting this way when you’re not in front of a screen. It’s impossible to breathe optimally. Also, when we anticipate or strongly focus on something, we inhale. That inhale is usually followed by an exhale. Except, this isn’t the case, when we’re in front of a screen. At least 80% of the people I observed, just like me, appeared to have compromised breathing when in front of a screen.

I followed this up with “dining room table science.” I’d seat someone at my dining room table, wire them up, ask them to do email, do a web search, to text, and I tracked their pulse and breathing. 80% of the people I tested had compromised breathing.

Chronically compromised breathing puts us into a state of “fight or flight.” In a state of fight or flight, our bodies dump stress hormones. Our bodies are accustomed to moments of fight or flight – we hear a noise, we inhale, listen carefully, and exhale when we determine we’re safe. We are preparing to run from a tiger. When we’re interacting with screens, we have chronically compromised breathing. Our body floods with stress hormones and then, because we’re not being chased by a tiger, our bodies bathe in those stress hormones. In a state of chronic fight or flight, we feel increased anxiety, we lose our sense of satiety and can experience compromised digestion, and compromised immune function.

After talking with neuroscientists, psychologists, researchers, and physicians, I gave this a name because I thought naming it would help raise awareness. I called this Email Apnea or Screen Apnea.

I was particularly interested in those who didn’t have screen apnea. My favorite conversation was with a music teacher. He explained that beginning music students often lean into an instrument, almost trying to merge with the instrument. The teacher works with the student on posture and breathing and helps them learn how to stay “embodied,” so they can bring their full selves, body and being, into playing the instrument. My hunch is, that if we teach kids how to play an instrument, it will teach them skills that will support them in healthier use of personal technologies.

Here’s what we can do today, to give our bodies the air they need, in a world where personal technologies are here to stay:

- Awareness: When you look at a screen, take a minute to notice your posture and to notice your breathing before you start reading or typing.

- Take breaks: Every hour, take a 5 minute break. Walk around. Notice your breathing. Enjoy a glass of water.

- Box Breathing: Breathe in and out through your nose. Inhale to the count of 3. Hold to the count of 3. Exhale to the count of 3. Hold to the count of 3. Repeat.

- Exhale for twice as long as you inhale: Breathe in through the nose to the count of 4. Exhale through the nose or mouth to the count of 8. Repeat.

Screen apnea hijacks the autonomic nervous system because it puts us in chronic fight or flight. Healthy breathing techniques help us reset the autonomic nervous system.

We love and hate our personal technologies. They set us free. They enslave us. As long as we’re spending hours every day in front of screens, we need to stay aware of our breathing.

A Story

Sharon Salzberg Talks About Real Love

My blog frequently discusses attention and also embodiment. And these themes play an important role in Sharon Salzberg’s newest book, Real Love. I found this to be a particularly lovely and comforting read, filled with stories and sweet practices.

1. What prompted you to write a book on love? In your wildest dreams, what impact might it have, for those who read it?

I’ve always been moved by love. I also, looking back on my writing, seem to have a fascination with reclaiming words that have, in my view, become something other than what I’ve always taken them to be, thereby losing some of their transformative power. I’ve long said I feel we are living in a time with a degraded understanding of love, and a blunted sense of aspiration in imagining what might be possible. But it hasn’t been that long. Look at photos of freedom riders in the civil rights movement praying before getting up and going to register black people to vote in the south – and getting beaten and tormented. They are connecting to a power of love so that they can remain non violent. That movement didn’t describe love as sentimentality, or over romanticized. In my wildest dreams I’d like the book to seriously help redeem the word, and return it to us as an enormous strength. I’d of course like people who read the book to find greater love for themselves and a greater sense of connection to others. It would be a far less lonely, more united world.

- You write about embodiment and love. How does embodiment contribute to our sense of safety and our capacity to love ourselves and others?

An area of research I’m trying to investigate more is the relationship between interoception (perceiving your inner state through awareness of body sensations) and empathy. I’ve seen studies with conflicting results, but it makes sense to me that we are far more attuned to our own emotional landscape if we can experience it through our bodies, and the more we are attuned to ourselves the more we can attune to others. I also keep coming back to love as connection – not as liking, or adoring, or approving of but connecting to. The first connection we need in order to live more fully is with our bodies.

- A friend of mine was recently diagnosed with breast cancer and has completed chemo, and is now getting radiation. She’s often ashamed of being ill and angry with her body, feeling limited and betrayed due to this illness. Her mind knows that being more loving to her body would be best, but she struggles with this. What do you suggest?

It takes a lot of awareness to look at the often cruel conditioning of this society which says we should be in control of all things at all times and if we’re sick or afraid, we blew it. We need to look at that conditioning, step back from it, and look honestly and rigorously at what is strength, really, and is love actually as often portrayed — simpering and ineffectual? Because that’s what we’re taught.

If you feel bold enough to experiment, you can send lovingkindness throughout your body…which doesn’t mean you are pleased with your diagnosis or you want it to triumph, at all. It’s recognizing that integrating all of one’s experience into a whole, seeing life working through us even in an illness, might well be the healing note we need.

- The election has been hard on families and friends when there are strongly held differing political views. Fear, pride, anger, and a host of emotions overwhelm any feelings of love. What advice do you have for people in these situations?

Something that is very hard to believe, or remember, is that we can love someone without at all liking them. And love, the generosity of the spirit that wishes that someone could have a happier, more connected life, doesn’t mandate any specific action: smiling, saying yes, giving in, trying to please, or having Thanksgiving dinner together. There is such a thing as tough love, or fierce compassion. In times of great division, and fear, it is very important to also take care of oneself. So we are looking for a really exquisite balance: love and compassion for ourselves and others; love for someone alongside the determination to do all we can to counter their views and not accede power to them if we believe they are really wrong, or harmful. We are not just living in a time of hyper -partisan views, we are also living in a time where you might wake up in NYC and go to get on the subway and the subway car walls are covered in swastikas, your mosque may be a terrorist target, or your African American son or daughter might be stopped by the police and become our latest, shameful tragedy. Adding more hatred to the mix doesn’t seem like it will get us anywhere.

- Many of us live with densely packed schedules day in and day out. What can we do with short patches of time, time during a commute, time in rush hour traffic, etc, to cultivate love?

We can remember to breathe, first of all. We can use awareness of our breath as a vehicle to return to ourselves, return to the moment, instead of being lost in rumination about the past or anxiety about the future. When we return in this way, we also return to our values, to remembering what we really care about most in any situation. If we have set an aspiration for that to be love, we will return to love.

We can also look around any conference table, subway car, or room, silently recalling, “Oh, you want to be happy too.” “And you want to be happy too.” It’s quite useful to reflect that everyone actually does want to be happy, we want a sense of belonging…. somewhere, in this body, on this earth. We all want connection. It’s the force of ignorance, believing so many myths and mistaken notions, that leads us astray. But remembering that we all do want to be happy is another way to return to love and compassion.

- What are the obstacles to forgiveness? How can embodiment contribute to forgiveness?

One of the strongest obstacles to forgiveness I’ve seen is a distorted notion of what forgiveness is. As my friend Sylvia Boorstein would say, “Forgiveness is not amnesia.” But we kind of think it is, often, that it is the same thing as saying what happened doesn’t matter. But maybe it matters quite a lot. Forgiveness is more like connection to something other than the incident – the truth of change, or a bigger picture of life.

I’ve also heard many inspiring stories of what I would call forgiveness, which end with the statement, “But I’ll never forgive.” Once I was teaching with a colleague, who gave a talk on forgiveness. One of the retreat participants, who clearly was struggling with lots of physical discomfort, came up to me to complain about what she, my colleague, had said. He then told me the story of surviving a terrorist attack but being in continual pain. He said, “I will never forgive, but I have learned that what is absolutely essential is to stop hating.” I’d call stopping hating forgiveness, but if he didn’t want to, that was ok with me!

Embodiment helps in that we can be sensitive enough to feel the burden chronic hatred is adding to what is already hard to bear – chronic pain. We can feel the difference, and make a choice for less suffering.

- Let’s talk about social media and real love. We spend so much time on our phones, laptops, Facebook, Twitter, and email. How does the time and attention we spend online effect our ability to love, and to cultivate the capacity for loving?

I think it depends on what you do on social media. Are you crafting a highly curated life, so much so that you feel inauthentic, or are you learning things about types of people, say those living in another country, you might not otherwise ever have known?

A professor friend of mine told me once he was worried about his students, who seemed to largely use their social media platforms to impress others with their, oh so perfect lives, and have them feel badly about their own lesser attempts at a life. As he put it, “no one posts a photo of their mediocre lunch.” I told him that might be an age thing, as most of my people seemed to post about their shoulder surgery etc. If your experience online is that you feel lonelier than before you signed on, there is something important to look at there. And of course we all need to look at how often we are glued to our devices…or we might actually not connect to the people we’re actually having lunch with at all!

- How does our time online contribute or take away from our sense of embodiment? What do you recommend we do about this?

Some people describe almost a kind of dissociative state if they stay online for a long time. I call it my fugue state. It’s definitely not embodied. Linda, you described email apnea, which seems part of the same bundle of tendencies. I think people confuse this with a flow state, which might feel as spacious as the fugue, but not as spacey. For every level of our well being, physical, mental etc, I’m told it is good to stand up every half an hour…so I’m about to do that right now.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on Sharon’s new book. Feel free to comment.

We’ve Got Rhythm

At the Near Future Summit 2017, I organized and moderated a capsule on Cycles and Rhythms. After years of studying the psychophysiology of our relationship to technology (how our attention, emotions, and physiology (breathing, etc.) are impacted by the way we use technology today), I realized that, at a deeper level, this all relates to the rhythms of the body. And the body is all about rhythm!

For starters: our gait, pulse, respiration, heart rate variability, organs, cranial rhythms, and our circadian rhythms, play a significant role in our health. Just as our bodies are all about rhythm, our planet, too, is all about cycles and rhythms.

Here’s my blog post from Medium.com on the session.

A few more words (and links!) on the Near Future Summit…

The World Positive area on Medium covered a number of the capsules at the Near Future Summit

For me, attending this event, was one of the most uplifting and optimistic experiences ever. Presenter after presenter shared break through technologies from CleanTech and urban farming to medicine, and from the treatment of PTSD to anti-recidivism.

If you have a moment to look up any of the following speakers, you’re likely to discover some extraordinary projects and startups:

Medicine: Dean Kamen, Osman Kibar, Nina Tandon

Food/Urban Farming: Tobias Peggs

CleanTech: Ben Bronfman, Etosha Cave, Ilan Gur, Molly Morse

Social Responsibility and Community Building: Cameron Sinclair, Yosef Ayele, Lindsay Holden

Cycles and Rhythms: Satchin Panda, Marko Ahtisaari, Dave Gallo, Li-Huei Tsai

PSTD: Rick Doblin

Criminal Justice Reform: Valerie Jarrett, Scott Budnick, Catherine Hoke, Lynn Overmann

Enjoy!!

Thinking about Metrics

Our lust for analytics sometimes divorces us from our humanity.

We have “superpowers” that are mysterious and challenging to quantify, and, that are at the heart of who we are as human beings.

Only with mutual respect for both the metrics and the mysteries will we thrive as a species.

This is all top of mind for me, at the moment, as I engage with the education non-profits I work with, and also with a few health projects.

In education, how do we “measure” (or even document) curiosity, engagement, passion? These are qualities that strongly contribute to success.

For health, what are the qualities that contribute to being able to maintain a positive attitude and persist toward positive behavior change as needed?

Please feel free to offer your own thoughts and experiences.

What’s Interesting?

A young woman was quite burned out after many years in a job to which she had given her heart and soul. A colleague described the work as, “Throwing toothpicks at dragons.”

I began to mentor her as she stepped into her transition out of the job and into, she knew not what. She could hardly imagine what she wanted to do next.

I gave her an assignment:

Every day, text me about something you notice or learn that is interesting to you. Write as much as you like.

She sent me daily texts and she started to notice a few things. She noticed that she was most likely to notice human behavior. When she realized that, she made a point of working to notice design, objects, and how things worked. She went from noticing people’s attitudes and behavior around Zika in Miami, to how escalators worked. She realized that, after a few days, she shifted from worrying about her future, to being in the present, curious about the world around her, and curious about the sentient beings in that world.

To give credit where credit is due, I first learned about this exercise from friends who required each of their children, every night at dinner, to share something interesting. The penalty for not doing so? A quarter in the jar.

What are you noticing?

What Would You Do?

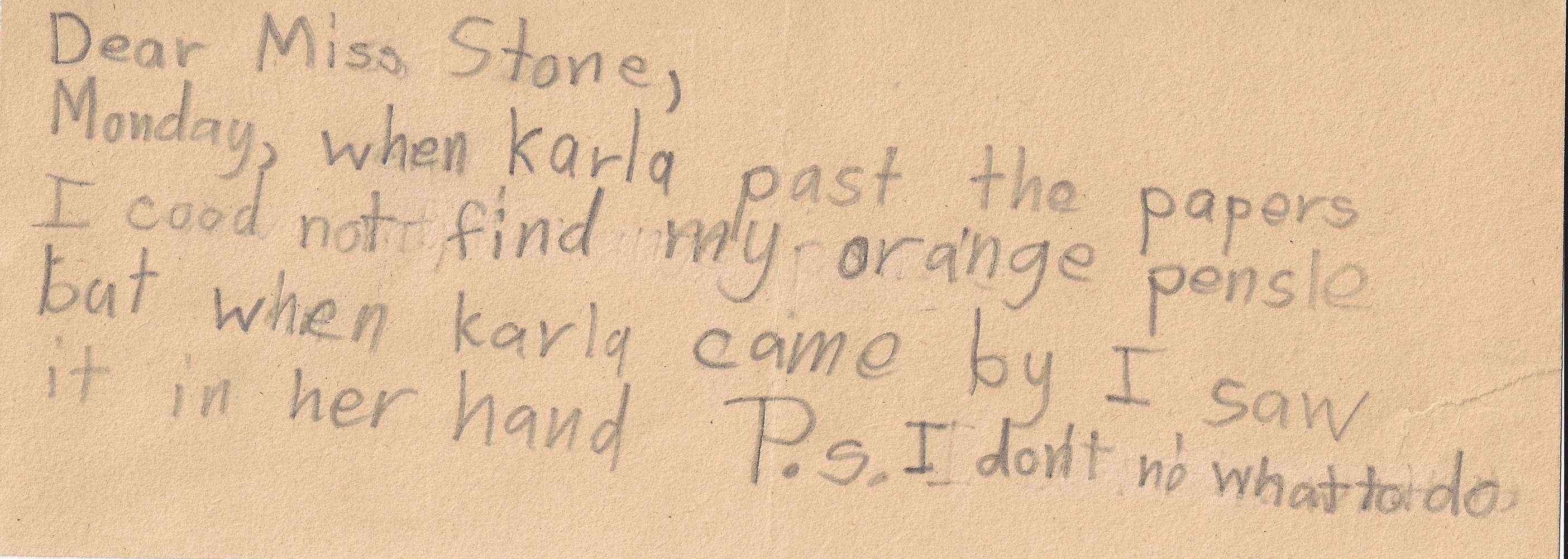

Note from a Second Grader

Between 1978-1986, I was a teacher and, later, a children’s librarian. I wrote the children notes and they wrote back to me.

A devastating fire wiped out most everything in my apartment in January 2016. I’ve been working through smoky documents that were salvaged, and found notes from the children that I had saved.

Bullying today seems nastier and more viral due, in part, to social media. When I discovered this note, I asked a few people, if Karla had taken their pencil, what would they have done? What would they recommend to Rachel, the sweet second grader who wrote this note.

What would you have done (as a second grader)? What would you suggest to Rachel?

The Genius of Attention: Making Peace with Bossy Mind

I am at the airport, in conversation with a man who is deaf. He is speaking, and I’m struggling to understand his speech. I’m distracted. My flight will board soon, and I’ve injured my knee, so I’ll need extra time to board and don’t want to miss the announcement.

He is telling me that he is going to see his 95 year old mother. I notice my distraction and make a decision to shift into paying full attention to this man who seems so interested in social contact. Over the years, I’ve come up with a simple tool to help me tune in to a conversation when I might otherwise be distracted.

I look at the man, noticing his eyes, his facial expressions, his gestures, and his strong desire to connect. I start noticing what I like about this man. As I do this, everything in the background falls away, and I see and hear him. He is an acupuncturist. He loves his mother who is very frail. He struggles with back pain and will also be boarding early.

Before I started using this tool of noticing what I like about a person with whom I’m in conversation, when I felt distracted, my Bossy Mind would direct my distracted mind to FOCUS! This process didn’t bring me into the moment, and into connection, in the same sweet way as noticing what I liked. Bossy Mind nearly always made me feel more anxious and more distracted.

Have you noticed that Bossy Mind is directing the current conversation about attention? “I’m distracted! I’ll never get it all done! I’m addicted to my phone!” This is Bossy Mind talk. Those newspaper headlines announcing: Addicted to Distraction; that’s Global Bossy Mind talking.

Attention, emotion, and breathing are very strongly related. When Bossy Mind owns the conversation and takes us into fear: “I’ll never get it done;” and distraction: “Why have you started ten emails and finished NO emails?!,” our breathing often becomes much shallower. When Bossy Mind revs up its internal dialog, the negativity and judgment often prompts negative emotions, making it more challenging for us focus and attend.

If athletes had a steady stream of Bossy Mind telling them they were distracted, needed to go faster, needed to focus, they would lose the race, drop the ball, and lose the game.

It turns out that with positive emotions, liking and loving, our breathing slows and can become deeper. Further, feelings of gratitude, felt in the whole body — embodied gratitude – can also slow and deepen our breathing, and bring our attention back to the present moment.

I used to think Bossy Mind, the wizard of distraction and overwhelm in my head, needed to be killed, or, at least silenced. Instead of raising a sword to slay Bossy Mind — because I guarantee you, Bossy Mind has a much bigger sword than you have – just, graciously, give Bossy Mind a seat at the table, then gently turn your attention in the direction of the noticing exercise below.

There is a Bossy Mind in every one of us. It needs a seat at the table and it will demand a seat whether you like it or not. But it does not need to be dancing ON the table, stealing the show. Making peace with Bossy Mind is a step toward being an “Attention Genius.”

Here are some things to notice when Bossy Mind is trying to take over:

- Notice what you like about another person, about your day, or about where you are.

- Notice beauty around you.

- Notice how you are safe.

- Notice the way your feet feel on the floor, the way the chair supporting you feels.

This might take 10 seconds. It might take a minute.

Bossy Mind is the Frito Bandito, the Hamburglar of our Attention. Bossy Mind is also part of who we are, and in accepting that graciously, and turning toward our liking, loving, appreciating, safe selves, our attention is ours to channel as we choose.

Stone, Kaplan, Nusbaum, Gallagher

Email Apnea on CBS

Are You Breathing? Do You Have Email Apnea?

It’s believed that many of us spend seven hours or more in front of screens each day. In 2011, researcher Emmanuel Stamatakis, found that “…even those who exercise can’t overcome the detrimental effects of too much screen time,” More here.

Ergonomists offer helpful suggestions regarding desk/computer setup and posture tips. Is that enough? How might screen time be affecting us and what else can we do to support health in our technology saturated lives?

In 2007, I was struggling with chronic respiratory infections and my MD suggested I study Buteyko breathing.

The Buteyko technique has been well-researched in Australia, the UK, and Russia, and has been shown to be very effective for people with asthma. Every day, I would do my Buteyko exercises before heading to my desk to work on email, research, and writing.

I noticed, almost immediately, that once I started to work on email, I was either shallow breathing or holding my breath. I paid attention and noticed that, day after day, this was the case. When I would get up and walk around, my breathing was completely different than it was when I was working on my computer.

I spent seven months observing and talking with others, and even tested friends at my dining room table, using a simple device that tracked pulse and heart rate variability (HRV). I also spoke with researchers, clinicians, psychologists, and neuroscientists to get a sense of what happens to our physiology on cumulative shallow breathing and breath holding.

I gave this a name: email apnea or screen apnea, which means, temporary cessation of breath or shallow breathing while working (or playing!) in front of screens.

I also noticed that only about 80% of the people I observed and tested had email apnea. Twenty percent did not have it. I became very interested in the 20%! The people who didn’t have email apnea were:

Dancers

Musicians

An IronMan triathlete, and other high performance athletes

A Test Pilot

When I questioned these people, I learned that they had been taught breathing techniques to manage their energy and emotions.

What happens to the body on email apnea?

There are very few studies that look specifically at HRV and physiological changes when we’re working at a screen.

Here they are:

- In 2009, Dr. Eric Peper, a researcher and Professor at UCSF, noted “sympathetic arousal” in college students texting messages on mobile devices. http://bit.ly/1tdF0BZ

- Researchers, Gloria Mark, Stephen Voida, and Anthony Cardello, made headway formally validating the impact of email, using heart rate variability (HRV) testing. http://huff.to/1pvbzYZ

In other research that looks at cumulative shallow breathing and breath-holding, here’s what I learned:

Drs. Margaret Chesney and David Anderson, formerly of NIH, demonstrated that cumulative breath holding contributes to stress-related diseases. The body becomes acidic, the kidneys begin to re-absorb sodium, and as the balance of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and nitric oxide becomes compromised, our biochemistry is thrown off.

Nitric Oxide (not to be confused with nitrous oxide, the “laughing gas” used in the dentist’s office) has been implicated in immune function, learning, memory and cognition, sleeping, weight, feeling pain, and inflammation.

With email apnea, or compromised breathing, we tend to go into a “fight or flight” or stressed state. Consider: when we’re afraid, we inhale and hold our breath. We become hyper alert to noises and motion. The body resources itself to run from danger.

In a fight or flight state, the sympathetic nervous system, or the fight or flight nervous system, is activated and causes the liver to dump glucose and cholesterol and the heart rate increases. We crave sugar and carbohydrates.

If you notice that you have email apnea, what can you do?

1. Awareness

The next time you look something up on your smartphone, or catch yourself responding to a text or email, notice: Are you breathing or holding your breath? Are you aware of your whole body? Or are you mostly aware of the keyboard, your fingers (and your typos!)? Are you holding yourself stiffly or does your body feel relaxed?

2. Take a break!

Get up once an hour for at least 5-10 minutes. Walk around and take a break. In Finland, students take a break every 45 minutes for 15 minutes and this has been shown to be effective.

3. Dance

Dancing is a terrific exercise. It can help with breathing, posture, and moving to rhythm.

4. Sing

Singing is a great way to learn breathing techniques and to improve lung capacity.

Earlier posts on email apnea:

Email Apnea; first posted 2/2008

From Email Apnea to Conscious Computing

Try This! Wild Exercises for Adventurous Travelers

My friend, Julia Cross, a brilliant dancer, demonstrates how to get exercise in flight. What fitness program would make it possible for the rest of us?! Happy Holidays and safe travels!

A Discussion of Essential Self Technologies

This discussion of Essential Self Technologies was presented April 10, 2014, at the MIT Media Lab.

Special thanks to Pattie Maes for hosting, to Alex Bodell and Anthony Zorzos for helping with the demo technologies, and to Karthik Dinakar, who provided video and tech support.

(Yes, I mis-speak for a moment at the beginning. Oops! The sympathetic nervous system refers to our “fight or flight” response. The parasympathetic nervous system refers to our “rest and renew” or “rest and digest” response.)

Cute Cats Redux

Ethan Zuckerman, who is wise, kind, and brilliant, posits that people have a preference for using the Internet for banal activities, like surfing for “cute cats.” It seems true that Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, and the like, are, indeed, rife with cute cats. I’m beginning to believe there is a deep explanation for that. I’m proposing a theory hereby referred to as Cute Cats Redux.

Here’s a little background:

In 2009, I was talking about email apnea and showing the Heartmath EmWave technology at a Foo Camp. Before passing the EmWave around, I demonstrated it. The EmWave shows, using red, blue, and green colored lights, the level of stress one is experiencing.

I explained that, to reduce stress, one could use certain types of breathing to get into a more balanced autonomic state. Only, even as I was using the suggested breathing technique, I was _not_ shifting states. The light was red. Red. RED.

I looked at the audience and said: “There’s actually another way to do this. When we evoke feelings of love and appreciation, it can also bring us into a more balanced autonomic state.” I looked around the room and saw so many people I admired and appreciated: Matt Mullenweg, John Hagel, Kathy Sierra, Bunnie Huang, Dan Gould, Sara Winge, and so many others.

Then, my eyes settled on Matt Mullenweg. Matt had very kindly come up to me at a conference a few months earlier, and mentioned that he enjoyed my writing, and when I was ready to move off my very broken JotSpot Wiki, to WordPress, that he’d be happy to help me. I was so moved by this – both emotionally (and literally! I made the switch and Matt was awesome!).

I started, “Matt, thank you so much for your kindness – for…” Before I could even finish the sentence, the audience gasped. GREEN!!! Eye contact, appreciation, and a few words, had shifted my autonomic state instantly! The audience SAW the power of emotion. Of course, with the emotion, my breathing and attention state also shifted. I was more relaxed. It’s all wired together: attention, emotion, breathing.

A few months after that, I was showing a senior executive how to use the EmWave to become more aware of her stress levels and to learn to better manage this. When breathing techniques didn’t work to help her shift out of a stressed state, I suggested she think about something she loved. Her husband was standing nearby. For a moment (she explained later), she focused on her husband, then sighed, and said, “Honey, I’m going to focus on the cats.” Green! Instant green!

Fast forward to March 2014. I’m being interviewed by Erin Anderssen, a journalist. She mentions that it can be challenging to shift from red to green when she’s using the EmWave. I tell her the story from 2009. Then it hits me!

What if all the cute cats and dogs on the Internet are in some small way, evoking momentary feelings of love and appreciation? What if looking at these images is as beneficial as a “breathing break.” What if cute cats and dogs make us kinder and more empathic as we hunch over our personal technologies for hours on end? What if we are self-soothing and bringing ourselves back into a kind of spiritual homeostasis when we look at and share these images and videos.

It turns out, there’s science to support the Cute Cats Redux theory. There’s a database of images called the International Affective Picture System, compiled by researchers Margaret Bradley and Peter Lang. This calibrated set of photos tracks affective consequences, and positive and negative responses to photos. Negative examples include: a spider, a baby with a tumor, and an automobile crash with injured people. On the positive side, there’s a category referred to as “cute.” Cute includes the old couple on the park bench holding hands and watching the sunset, as well as kittens and puppies. All these produce positive affect.

Looking at those cute cats and puppies is not a waste of time. It’s self-soothing. Just as we have a physical homeostasis that supports healthy regulation of bodily functions, I believe we have a spiritual homeostasis that can draw us, both individually and collectively toward what heals us. Cute Cats Redux.

This post is dedicated to Ben Huh, Cheezburger, and to a very funny guy who sent me a video of him singing a sweet song to his cat.

What Part of You is Free?

This post was written several years ago. I’m feeling great these days and ready to post some of the things written in darker moments…

From January 2010

I’m lying in bed and the right side of my body is frozen. I’m right-handed. I want to get up and the thought alone isn’t getting me there. I remember something my doctor said, “When you wake up, pay attention to what is working. Put all your attention on that.”

I scan my body. My left arm is great. Okay, left arm, show me what you can do. I reach to grab one of the headboard spindles, and use my left arm to roll over and hoist myself up. My left leg is working pretty well, too. I lean against the wall and drag myself into the bathroom. Home run. I may be right-handed, but my left arm rules.

A few years ago, my friend, Mary Jane, was telling me about someone she had coached. The woman kept diving into the same story, the same limitations, and the same struggles. Mary Jane would listen and ask questions. At one point, in a face-to-face meeting, Mary Jane took the woman’s arm and told her to try to get away. The woman pulled and pulled with the arm Mary Jane was holding, then, gave up. “I’m stuck,” she said, committed to stuck-ness.

“What part of you is caught?” Mary Jane asked.

“Easy,” the woman responded, “my arm.”

“What part of you is free,” Mary Jane coached.

“Wow. The rest of my body!”

“How can you use the rest of your body to free yourself?”

The woman was quickly free.

As I fell back into bed, I wondered why mind always found limitations quickly and was blind to freedom.

One of my favorite mentors and teachers, Byron Katie, offers:

“Life is simple. Everything happens for you, not to you. Everything happens at exactly the right moment, neither too soon nor too late. You don’t have to like it… it’s just easier if you do.”

Falling in Love (How To)

A few years ago, in a conversation with a friend, I caught myself paying more attention to another, nearby conversation. Realizing I was missing the moment to connect with this friend, I created a “game” for myself to counteract the distraction. Now, as much as possible, when I make a choice to be in conversation with someone, I assign myself the task of noticing what I like about that person. This attunes my listening, and softens my attention into a state I call “relaxed presence.” It opens me into a receptive, present moment state.

In doing this, I find myself falling in love all day long.

For me, this “game” is more powerful than listing what I’m grateful for or reminding myself of the power of unconditional love and compassion. Going from the general to the specific, is immediate and powerful.

Tonight, at dinner, I fell in like/love with the person next to me, a serial entrepreneur and social entrepreneur with a strong sense of integrity, warmth and kindness, curiosity and creativity.

The path toward compassion and unconditional love starts here.

Our Powerful and Fragile Attention

What if I told you that the way we are talking about attention is part of the problem today? Our conversation about distraction, multi-tasking, and the stern command to focus actually creates a level of stress, anxiety, and shame.

Headlines read: Dangers of Digital Distraction! Taming the Distraction Monster! Time to Unplug! This conversation stresses us in a way similar to the techniques magicians and con artists use to create misdirection. As we consider how distracted we are, we shame ourselves with messages like: “I should unplug!” “I have too much to do!” “I’m distracted!” “I have to focus!”

All of these thoughts, all of this stress, zaps our attention bandwidth. We twist in the winds of our own misdirection. Isn’t it ironic that even in our efforts to manage our attention effectively, we are, instead, contributing to stress and misdirection!

If we don’t consciously choose where we want to direct our attention, there will always be something in our path tomisdirect it. From the news, to pickpockets, to Facebook — every choice we don’t make is made for us.

If we want to harness the superpower that is our attention, instead of talking about distraction and a need to unplug and disconnect, let’s talk about what it is we choose to connect to. As we reach for what we prefer, we can stop stressing and shaming ourselves regarding what it is we’re getting wrong.

The Time We Have (in Jelly Beans)

http://ashow.zefrank.com/episodes/128

My friend’s 16 year old son stopped playing video games. Cold turkey. From hours a day in front of the screen one day to those same hours spent with friends ever after.

“Why did you stop?” his mother asked.

“Jelly Beans. My life in jelly beans.”

Thanks to Ze Frank for creating this powerful video!

Choreograph Lively Dinner Conversation

I started hosting dinner parties when I was 12. I enjoyed cooking and especially loved great conversation. Over the years, I started to notice that even with fourteen fascinating people at the table, sometimes the conversation was like fireworks and sometimes it fell flat.

I wanted to figure out an algorithm for dinner party seating. Was this magic? Or was there a formula? I was certain there was a way to ensure great conversation.

I think of dinner table conversation as “pinball.” If the ball stalls or goes down the drain, the game loses energy. If an energetic conversation is happening between two people sitting across from each other, the ends of the table “die.”

It’s an art! It’s a science! It’s fun. Please try it out and let me know how it works for you!

Basic Rules

»Eight to 14 people per table works best.

»Never seat friends next to one another.

»Ignore the old etiquette of alternating males and females.

Strategy

»Sort place cards into four “energy density” piles: H (high), M (medium), L (low), and ? (wild card).

»Assign the H guests first. Seat them diagonally from one another. Never seat H people directly across from each other.

»If you have guests with strong opposing views, seat them diagonally from each other, too.

»Seat the L people next to the H people. When conversation bounces around the table, The Ls will be more inclined to participate because of their proximity to an H.

»Scatter M and ? guests among the remaining open seats.

The piece below was first published by Wired in August of 2006

Aspen Ideas Festival: “Information Overload”

Can we be productive in a world full of constant updates? Will we adapt or will we burn out? Linda Stone and William Powers at AIF 2011

The Essential Self: Health Beyond the Numbers

“What are you tracking?” This is the conversation at Quantified Self (QS) meetups. The Quantified Self movement celebrates “self-knowledge through numbers.” In our current love affair with QS, we tend to focus on data and the mind. Technology helps manage and mediate that relationship. The body is in there somewhere, too, as a sort of “slave” to the mind and the technology.

In our relationship with technology, we easily fall out of touch with our bodies. We know how many screen hours we’ve logged, but we are less likely to be able to answer the question: “How do you feel?”

The full post is here, and suggests a new movement, alongside the Quantified Self movement. This new movement is called: The Essential Self.

What might the tools and technologies of this new movement look and feel like?

Passive, ambient, non-invasive technologies are emerging as tools to help support our Essential Self. Some of these technologies work with light, music, or vibration to support “flow-like” states. We can use these technologies as “prosthetics for feeling” — using them is about experiencing versus tracking. Some technologies support more optimal breathing practices. Essential Self technologies might connect us more directly to our limbic system, bypassing the “thinking mind,” to support our Essential Self.

When data and tracking take center stage, as is the case with most Quantified Self technologies, the thinking mind is in charge. And, as a friend of mine says, “I used to think my mind was the best part of me. Then I realized what was telling me that.”

Here are a few examples of outstanding Essential Self technologies; please share your examples and experiences in the comments:

- JustGetFlux.com

More than eight million people have downloaded f.lux. Once downloaded, f.lux matches the light from the computer display to the time of day: warm at night and like sunlight during the day. The body’s circadian system is sensitive to blue light, and f.lux removes most of this stimulating light just before you go to bed. These light shifts are more in keeping with your circadian rhythms and might contribute to better sleep and greater ease in working in front of the screen. This is easy to download, and once installed, requires no further action from you — it manages the display light passively, ambiently, and non-invasively. - Focusatwill.com

When neuroscience, music, and technology come together brilliantly, focusatwill.com is the result. Many of us enjoy listening to music while we work. The folks at focusatwill.com understand which music best supports sustained, engaged attention, and have curated a music library that can increase attention span up to 400% according to their website. The selections draw from core neuroscience insights to subtly and periodically change the music so your brain remains in a “zone” of focused attention without being distracted. “Attention amplifying” music soothes and supports sustained periods of relaxed focus. I’m addicted. - Just for fun, use a Heartmath EmWave2 to track the state of your Autonomic Nervous System while you’re listening to one of the focusatwill.com music channels.

From the Atlantic: Interview with James Fallows

Jim Fallows asked me to talk with him about the future of attention. I wanted to share the links for the short version that appeared in the magazine, and the longer version that appeared online.

The short version, followed by a link:

From the time we’re born, we’re learning and modeling a variety of attention and communication strategies. For example, one parent might put one toy after another in front of the baby until the baby stops crying. Another parent might work with the baby to demonstrate a new way to play with the same toy. These are very different strategies, and they set up a very different way of relating to the world for those children. Adults model attention and communication strategies, and children imitate. In some cases, through sports or crafts or performing arts, children are taught attention strategies. Some of the training might involve managing the breath and emotions—bringing one’s body and mind to the same place at the same time.

Here’s an excerpt from the full interview, which Jim posted on his blog:

We learn by imitation, from the very start. That’s how we’re wired. Andrew Meltzoff and Patricia Kuhl, professors at the University of Washington I-LABS, show videos of babies at 42 minutes old, imitating adults. The adult sticks his tongue out. The baby sticks his tongue out, mirroring the adult’s behavior. Children are also cued by where a parent focuses attention. The child’s gaze follows the mother’s gaze. Not long ago, I had brunch with friends who are doctors, and both of them were on call. They were constantly pulling out their smartphones. The focus of their 1-year-old turned to the smartphone: Mommy’s got it, Daddy’s got it. I want it.

We may think that kids have a natural fascination with phones. Really, children have a fascination with what-ever Mom and Dad find fascinating. If they are fascinated by the flowers coming up in the yard, that’s what the children are going to find fascinating. And if Mom and Dad can’t put down the device with the screen, the child is going to think, That’s where it’s all at, that’s where I need to be! I interviewed kids between the ages of 7 and 12 about this. They said things like “My mom should make eye contact with me when she talks to me” and “I used to watch TV with my dad, but now he has his iPad, and I watch by myself.”

Kids learn empathy in part through eye contact and gaze. If kids are learning empathy through eye contact, and our eye contact is with devices, they will miss out on empathy.

Both in the interview with Jim and later in a post for the Atlantic website, I talked about how we think about and measure productivity today: more work, faster pace, more efficiently, and how we might rethink productivity and how we measure it going forward.

Note that I’m not arguing against being productive. I’m asking that we re-consider how we evaluate productivity. Is it the number of emails we send and receive? The number of hours a child spends on homework? Read the excerpt and click on the link below. Please consider sharing your experience and thinking on this.

An unintended and tragic consequence of our metrics for schools is that what we measure causes us to remove self-directed play from the school day. Children’s lives are completely programmed, filled with homework, lessons, and other activities.. There is less and less space for the kind of self-directed play that can be a fantastically fertile way for us to develop resilience and a broad set of attention strategies, not to mention a sense of who we are, and what questions captivate us. We have narrowed ourselves in service to the gods of productivity, a type of productivity that is about output and not about results.

Q & A: Interview with Smart Planet

Q & A: Interview with Smart Planet

Here’s a snapshot of the Q & A I did recently with Rachel James of Smart Planet. For the full post and the comments, please click here.

You’ve held executive roles at Apple and Microsoft. Tell me about how you transitioned into researching our behaviors around technology.

When I was at Microsoft I started looking at what happens to our attention when we’re working with technology. Soon after this, I began researching on my own. One of the questions was: Are people managing their time or their attention? I did a fascinating set of interviews on management of time and attention and how this related to burnout.

How do you differentiate between managing our time and managing our attention?

The people I spoke with who worked in office jobs typically said they managed their time. Many of them had taken time management classes and had things carefully mapped out during the day. This included everything from how many minutes were spent in meetings, on email, on the phone, and with their children. Almost everyone who said they managed their time reported being overwhelmed and feeling burnt out.

When people reported managing their attention, they reported more flow states. It was really interesting. The people who were most likely to say they manage their attention –- artists, CEOs and surgeons — actually described a process of managing a combination of time and attention.

Many executives and CEOs said that if they didn’t manage their attention, they found they would deal with the little things and miss strategic opportunities. They said this was something they had to learn when they moved into the CEO position.

What exactly is a state of flow and why is it important that we find one?

I need to give credit to Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi for his brilliant work on flow. One of his books is called Finding Flow: Engagement with Everyday Life. It’s a phenomenal book.

What happens in a state of flow is you are concentrating, but not in a stressed way. It’s the same kind of attention you see in children when they’re engaged in self-directed play. When you watch 3-, 4-, 5- or 6-year-olds building blocks, you see they are fully engaged in the moment.

When you encounter a surgeon in a flow state, they are working right in the moment. They can notice something and change direction. If they simply stuck to the plan, they might begin a procedure and miss a new lesion, for example. In this flow state we are at optimum creativity. We are not bored, but we’re also not anxious.

Let’s talk about your work on the physiology of technology. What makes bringing technology into the broader conversation about wellbeing important?

Here’s what I noticed. As I was researching the differences between managing time and attention, I just so happened to begin taking a breathing class. I was dealing with a respiratory infection and my doctor wanted me to study a technique called Buteyko breathing.

Every morning, before sitting down at my computer, I would do 20 minutes of breathing practice. I noticed on day one, within five minutes of sitting down, I was holding my breath.

At that point I embarked on a study. I observed people using technologies –- a computer, iPhone –- and looked at what was happening to their pulse and heart rate variability and what that indicated about their breathing.

By early 2008 I came up with the phrases “email apnea” and “screen apnea” [which are interchangeable]. We tend to breath-hold or shallow breathe when we sit at a laptop. The computer becomes animated and we become less animated. Our shoulders and chest cave in, we sit slouched for extended periods of times. And it’s impossible to fully breath in that hunched posture.

When you are shallow breathing or breath holding cumulatively day after day, your body goes into a chronic state of fight or flight. You tend to crave carbohydrates and sweet foods because they give you energy to outrun a tiger. Seriously. Our thoughts turn to, “I need to get this done! I can’t get this done! Will I get this done?”

There’s another piece about the physiology of technology that hasn’t been talked about much to date. The effect sitting at computers has on our lymphatic system.

Lymph is pumped through our bodies with the movement of our feet and calf muscles. All this sitting is making it difficult for our bodies to do what it needs to do for natural detoxification.

Where has this research led you?

I started to notice that there was a tremendous amount of discussion around disconnecting. I find something about this conversation really troubling. It sounds like the conversation around dieting that doesn’t work: “I shouldn’t eat the cookie. I shouldn’t eat the cookie. I shouldn’t eat the cookie.”

When we think, “It would be great to eat an apple,” we do much better. Understanding which behaviors we want to build into our lives, rather than which behaviors we want to take away, is much more effective.

So how can we have a conversation about what we connect to? This will get us away from “Don’t touch the computer! Put the phone away! Don’t eat the cookie!” That’s a lot of ‘don’t’ to live with.

What is your take on our obsession with productivity? There are so many programs out there that take a parental approach to our self-micromanaging. Freedom, Isolator, Stay Focused… You take a much more embodied approach. Where would you like this conversation to land?

The 20th century was all about productivity. Man as machine. Man as faster and more productive. We were so excited by the industrial age. ‘More, faster, more efficiently’ — that was the conversation.

And that was what we measured — on the job and in our own lives. How many things on my list have I done? Our whole conversation was about output and quantity. I believe that the 21st century will be a return to what humans do best –- and this has to do more with engagement and flow, less with output and quantity. We have robots that are going to take over a lot of those ‘more, faster, more efficiently’ jobs.